“He he knew his body had lost the resiliency of his boyish years; for the first time he accounted how he would pay for all the little follies of youth. .. at seven, he had cracked his knee falling through the stable-loft floor: that came back to haunt him. The elbow he had affronted in weapons practice not five years gone, that afflicted his shoulder as well. The time Danvy had pitched him off over his head, the slip of the ice when he was twelve, the times his mother had warned him about leaping off the side of the staircase… you’ll break your feet, she had said, and he had not remembered his mother’s voice clearly in years, but he could now, in this long watch.” (p. 166 SFBC hardcover).

Many times the dice roll against the characters. Critical hits, the GM wisely using his monster’s abilities, traitors in the group, and the dice falling where they may, can lead players to experience all levels of pain that their super human characters can endure.

But what about when they’re not in combat? In combat, if you can spare it, take a few seconds to note critical hits and note how you describe them. Remind the player later of that pain. In most cases, the players probably will suffer only light scaring if even that thanks to quickly being healed through magic, but what of death? What if the players have to bring back one of their own? What marks will death leave on the player? Will it leave him with a stutter? With it leave him with a limp? Putting role playing elements in that have no game mechanics can give the players more ties to their own history in the campaign.

“He drew his sword and with it traced a Line of his own on the stones, slowly, surely, drawing the Line with the touch of the metal on stone, securing it with the touch of his boots on the floor and the strength of his wishes in the stones.” (p. 259 SFBC hardcover).

Many magic systems are tied into rite and ritual. In the new edition of Dungeons and Dragons (4th ed as of 2009 still), rituals are methods of using magic that often take time and do a variety of utility needs. However, most of these rituals are vaguely described in terms of how they’re actually performed as opposed to what they do. Like much else that is scant in 4e, this is an opportunity for the Game Master to put his own touches on the campaign or even better, have the players put their own personal touches on the setting. When a player tells you he’s using a ritual, ask him how exactly he goes about it. Ask what items are brought, ask when its performed, ask if there are any unique rituals and movements.

These things, following the old five W (who, what, when, where and why) along with how, can allow each character to have some unique traits that aren’t impeded by game mechanics and provides them with unique flavor.

“It threatens everything,” Tristen said, and could not bid Crissand avoid it: could not bid any one of his friends avoid it. It was why they had come, why they pressed forward, why they had gone to war at all, and everything was at risk.” (p. 282 SFBC hardcover.)

As the campaign progresses, it’s not longer enough to guard the town. It’s not longer enough to watch over wagons. It’s not enough to save the city nor the country. Sometimes the very nature of the world itself is at stake. Such gambits can be hard to pull off and should be near the maximum levels of the game’s limits, or when the Game Master or players know ahead of time that the campaign will be coming to an end. By letting the threat elevate to new levels, the GM can bring a sense of urgency to the campaign that a standard villain may lack. In this case, the true enemy is something beyond standard naming conventions, it’s beyond being merely an evil entity. Much like the One Ring from Lord of the Rings, it’s powers lie in corruption, but much like Sauron himself, the real power is always waiting in the background, waiting for its opportunity to rise, to strike, to take it all when the time is right.

Many times the dice roll against the characters. Critical hits, the GM wisely using his monster’s abilities, traitors in the group, and the dice falling where they may, can lead players to experience all levels of pain that their super human characters can endure.

But what about when they’re not in combat? In combat, if you can spare it, take a few seconds to note critical hits and note how you describe them. Remind the player later of that pain. In most cases, the players probably will suffer only light scaring if even that thanks to quickly being healed through magic, but what of death? What if the players have to bring back one of their own? What marks will death leave on the player? Will it leave him with a stutter? With it leave him with a limp? Putting role playing elements in that have no game mechanics can give the players more ties to their own history in the campaign.

“He drew his sword and with it traced a Line of his own on the stones, slowly, surely, drawing the Line with the touch of the metal on stone, securing it with the touch of his boots on the floor and the strength of his wishes in the stones.” (p. 259 SFBC hardcover).

Many magic systems are tied into rite and ritual. In the new edition of Dungeons and Dragons (4th ed as of 2009 still), rituals are methods of using magic that often take time and do a variety of utility needs. However, most of these rituals are vaguely described in terms of how they’re actually performed as opposed to what they do. Like much else that is scant in 4e, this is an opportunity for the Game Master to put his own touches on the campaign or even better, have the players put their own personal touches on the setting. When a player tells you he’s using a ritual, ask him how exactly he goes about it. Ask what items are brought, ask when its performed, ask if there are any unique rituals and movements.

These things, following the old five W (who, what, when, where and why) along with how, can allow each character to have some unique traits that aren’t impeded by game mechanics and provides them with unique flavor.

“It threatens everything,” Tristen said, and could not bid Crissand avoid it: could not bid any one of his friends avoid it. It was why they had come, why they pressed forward, why they had gone to war at all, and everything was at risk.” (p. 282 SFBC hardcover.)

As the campaign progresses, it’s not longer enough to guard the town. It’s not longer enough to watch over wagons. It’s not enough to save the city nor the country. Sometimes the very nature of the world itself is at stake. Such gambits can be hard to pull off and should be near the maximum levels of the game’s limits, or when the Game Master or players know ahead of time that the campaign will be coming to an end. By letting the threat elevate to new levels, the GM can bring a sense of urgency to the campaign that a standard villain may lack. In this case, the true enemy is something beyond standard naming conventions, it’s beyond being merely an evil entity. Much like the One Ring from Lord of the Rings, it’s powers lie in corruption, but much like Sauron himself, the real power is always waiting in the background, waiting for its opportunity to rise, to strike, to take it all when the time is right.

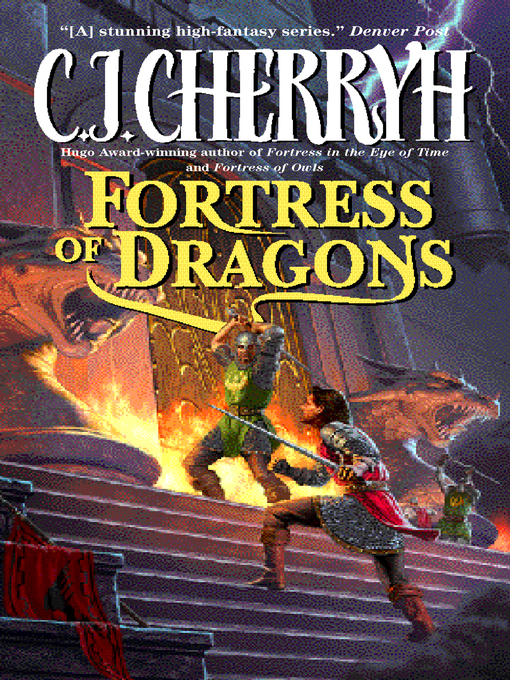

Fortress of Dragons ties up C. J. Cherryh's fantasy tale of friendship not only on a high note, but also on a note of future exploration. When ending your own campaigns, try to insure that even though all the immediate needs are filled that there is always the possibility of coming back to that campagin.

No comments:

Post a Comment