Sheepfarmer’s Daughter, Book One of the Deed of Paksenarrion, is in many ways a typical ‘farmer’ story. A character of humble origins goes out into the world and from a small point of knowledge, gains a greater understanding of how things work in the ‘real world’.

Note when I say famer, I don’t necessarily mean an actual farmer. For example, in the White Company, the scholarly monk of the series, despite having a plethora of book learning, discovers that the world outside his monastery walls isn’t quite the way it is depicted in the books.

Foreigners also fit into this category. While they may have a larger body of experience to draw on, their overall knowledge base of the current campaign is limited. One movie example of this would be Tom Cruise’s character in the film, the Last Samurai. He comes in with a body of knowledge. He is not ignorant to the ways of war. But in the ways of the Samurai?

This type of character is useful in a fantasy campaign for several reasons. The first is that it allows the Game Master to directly set the scene. If the player is one who has read sourcebooks and fictional material about the setting, all of that becomes “merely rumors.” After all, what does someone trapped on the farm truly know about how life on the outside is?

Outside of showcasing the growth of character, Sheepfarmer’s Daugher also has a great framing reference in the military mercenary company that Paks is a part of.

In many campaigns, there may be questions as to why all of the players are gathered. What links to they have to one another to keep loyal to each other? What method can the Game Master use to move the campaign forward.

A military campaign is an easy framing reference in that it allows the players to know each other right off the bat. It provides them with a common background. It gives them leadership and possibly other tangible benefits such as rivalries with other companies, that may be friendly or deadly series.

In Sheepfarmer’s Daughter, the companies tend to be broken up into the more honorable north companies and the more bandit like southern companies. A background element like this provides its own hook. In a fresh starting campaign with new players that are new to role playing, the Game Master can use an honorable company to provide mentors to explain how things work in the campaign.

Optionally, if only some of the players are new, the Game Master can allow those who are old hands to actually take the role of the mentors. Give them a few levels and abilities that the new recruits must train to match up with. But reduce their experience gained. In 3.5, this is self handled by the methodology of experience where lower level characters gain more than higher level characters.

The point isn’t to let the old hands lord over the new players, it is to allow the old hands an advantage in ability to showcase the world and setting and how the rules work, not to beat the newbies over the head with their power.

In addition, these mentors can act as a source of information for how things work in the ‘meta’ setting. For example, Sheepfarmer’s Daughter includes information on how the soldiers march, how they train, how they form rank and file, which weapons they use, and how they work in the world. Because the main character who is learning all of this is originally sheltered from such information, it allows the author to make large information ‘dumps’ to the reader without coming out on a sidebar or other aspect that can feel forced.

The other thing I’d like to mention about Sheepfarmer’s Daughter is that it is fairly internally consistent. The characters are aware that magic exists in the world. When they encounter it, they strive to overcome it. They don’t act like it’s the first time such magic has ever been used in the setting before. Some authors play with the readers in trying to keep magic mysterious by having things that would be obvious to characters who actually lived in the setting have no idea on how to react, or even about the existence of magic despite the fact that some of them may use it in the form of potions or magical weapons.

Lastly, in the novel, Pak’s is saved by ‘luck’ several times. This is an indication in the novel that there are higher powers looking out for the character. There are often numerous bits of advise for GMs in terms of ‘cheating’, allowing the characters to survive something that should have killed them. In many ways, this is one of the reasons why the GM screen is around. Not to cheat and punish the players. After all, the GM controls the whole of the world. It’s easier enough to throw an ancient red dragon at a group of first level characters.

Published in 1990, the DMGR1 Campaign Sourcebook and Catacomb Guide for AD&D 2nd edition notes on page 44, “Still, instead of killing the characters outright, he could throw something else at them, something equally deadly, but which will give them a chance to survive – if they’re clever.”

The real trick in doing this though is to never let the players know. If they feel that every time they are going to get into a potentially fatal situation the GM is going to save them, there is no fear of death and perhaps even a smugness about it. Always give the players the feeling that things could get much worse far too quickly for their liking.

Sheepfarmer’s Daughter can provide the reader with a good framing reference for a campaign but also allows the reader to see a bigger picture and this can be used as a tool to help move players outside of the military campaign once they’ve gotten the hang of it.

Tuesday, August 24, 2010

Sunday, August 22, 2010

Sheepfarmer's Daughter by Elizabeth Moon

While I still own many a book I have not yet read, I still find myself wandering off to Half Priced books. Because of all the books though, I’ve decided that if I’m going to buy a book, it has got to be coming out of the one dollar spinners they have located throughout the store. So I pick up the Deed of Paksenarrion Book One through Three, written by Elizabeth Moon.

I’ve never read any Elizabeth Moon. I figure for a dollar each, if I don’t like them I can give them to a friend and not worry about it.

Her writing is crisp. It gets to the point. It is easy to read. These things alone insure that I will finish the series.

But what struck me in the first few pages that I wanted to share it with the readers of the blog? It is not necessarily that it moves quick in terms of action or events, but rather how it moves.

The main character, a tall woman Paksenarrion, Paks for short, does not want to do as her father wishes and marry the pig farmer down the road and wants to join the military and serve thanks to tales told to her by her cousin. It happens quickly. Her initial signing isn’t made a big deal of. Her leader and trainer in her unit is very much a mentor role without being interested in her as a woman.

This to me, after reading books like Best Served Cold and the First Law, was like a breath of fresh air. Sometimes when I’m reading writers, I get the feeling that they just keep adding text and text and text and problems and problems ot make things more interesting instead of getting the story done.

For example, while reading this, I thought for sure she wouldn’t get away from her father. I thought for sure that she’s have some dire encounter on the road to joining the military that would make her question her motivations. I thought for sure that she would initially be turned away from signing up, that her mentor would be some puke who only wanted to bed her and dispose of her. None of those things happened.

It is not that bad things do not happen to the character, but rather, it does not seem like the entire setting is out to cause her harm. When she does encounter difficulties, there are those who are neutral on the subject, but follow the chain of logic and evidence as well as those who stand against her. It makes a nice breath of fresh air.

When as a game master you are about building your story, communication with the players is a good thing to keep the game moving in a direction that makes everyone happy. For example, if there was a female player who wanted to play a warrior and was using running away from home as a background, would the GM throw those things above in her way or, like Elizabeth Moon does, just use that as a launching point and get to the military and move on?

I’m not advocating not throwing issues into the players way. But knowing which issues are worth the time to spend in game and to engage the player with is a vital tool of having the players enjoy the game. There are some players who look forward to expecting the inevitable betrayal, of expecting their employer to turn on them at any moment, that the kindly old white wizard is actually the balrog in disguise. Indulge them in that as it is what they enjoy. For those who have a stated goal and want to get to it, try not to make it so difficult that it alters the character concept and background.

I’ve never read any Elizabeth Moon. I figure for a dollar each, if I don’t like them I can give them to a friend and not worry about it.

Her writing is crisp. It gets to the point. It is easy to read. These things alone insure that I will finish the series.

But what struck me in the first few pages that I wanted to share it with the readers of the blog? It is not necessarily that it moves quick in terms of action or events, but rather how it moves.

The main character, a tall woman Paksenarrion, Paks for short, does not want to do as her father wishes and marry the pig farmer down the road and wants to join the military and serve thanks to tales told to her by her cousin. It happens quickly. Her initial signing isn’t made a big deal of. Her leader and trainer in her unit is very much a mentor role without being interested in her as a woman.

This to me, after reading books like Best Served Cold and the First Law, was like a breath of fresh air. Sometimes when I’m reading writers, I get the feeling that they just keep adding text and text and text and problems and problems ot make things more interesting instead of getting the story done.

For example, while reading this, I thought for sure she wouldn’t get away from her father. I thought for sure that she’s have some dire encounter on the road to joining the military that would make her question her motivations. I thought for sure that she would initially be turned away from signing up, that her mentor would be some puke who only wanted to bed her and dispose of her. None of those things happened.

It is not that bad things do not happen to the character, but rather, it does not seem like the entire setting is out to cause her harm. When she does encounter difficulties, there are those who are neutral on the subject, but follow the chain of logic and evidence as well as those who stand against her. It makes a nice breath of fresh air.

When as a game master you are about building your story, communication with the players is a good thing to keep the game moving in a direction that makes everyone happy. For example, if there was a female player who wanted to play a warrior and was using running away from home as a background, would the GM throw those things above in her way or, like Elizabeth Moon does, just use that as a launching point and get to the military and move on?

I’m not advocating not throwing issues into the players way. But knowing which issues are worth the time to spend in game and to engage the player with is a vital tool of having the players enjoy the game. There are some players who look forward to expecting the inevitable betrayal, of expecting their employer to turn on them at any moment, that the kindly old white wizard is actually the balrog in disguise. Indulge them in that as it is what they enjoy. For those who have a stated goal and want to get to it, try not to make it so difficult that it alters the character concept and background.

Labels:

Elizabeth Moon,

Game Master,

Paks,

Player Characters,

Role Playing

Thursday, August 12, 2010

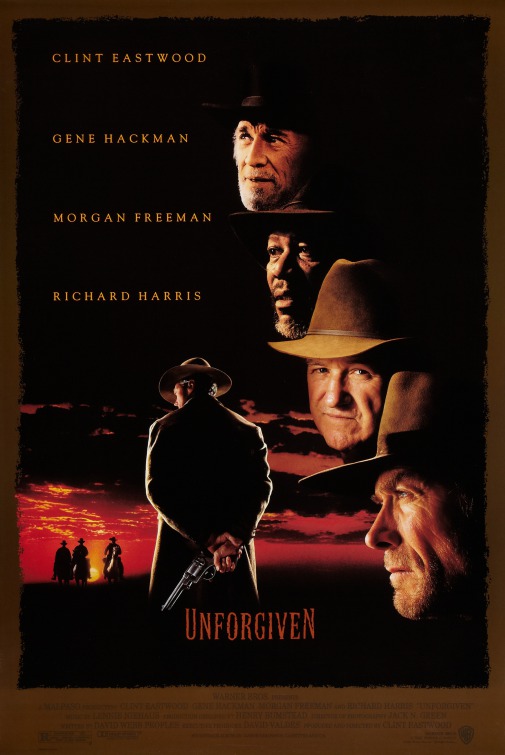

Unforgiven

Unforgiven is a classic Western movie. While the plot is fairly razor thin, it is one often used for adventures to begin with. “There is a bounty on this individual. Go collect it.”

The thing that makes Unforgiven however, is the atmosphere and the characters.

The atmosphere drifts in through names like the town, Big Whiskey and through little statements made here and there, like when someone mentions the billiards table was broken down for fire wood years ago. Or how technology isn’t there to solve every problem such as vision difficulties or simply having the hogs suffer flu.

But it is the background of the characters that helps the whole movie to gel. For example, the viewers are often introduced to characters not only through those characters actions, but by how the other individuals in the movie react to them.

When English Bob and his biographer are travelling along on the train and being taunted by one of the cowboys, another cowboy warns him that this fellow might indeed be English Bob and is not one to be trifled with. The audience is further granted a view of skills involved here with a pheasant shooting contest from the back of the moving train with Bob hitting eight and the cowboy hitting one.

But as in many setups, this is just a tease. You see, it’s a tease for the build up of Little Bill who is spoken of in near holy tones by his fellow law men. Was he scared? No. He’s a bad carpenter, but he ain’t scared. Indeed, Little Bill is so unafraid of English Bob that he gets the drop on him with a full posse and beats the crap out of him. This sets Little Bill up as a truly big bad.

One of the 4e DMGs has some advice on trying to showcase the strength of the big bad including allowing the players to take the role of the person going up against the big bad. This allows the players to first hand experience the gaming effect without the GM only having to rely on narration to showcase the strengths of the villain.

It is also the characters that move the story along. There is no dungeon to explore here. While there is a beautiful scenery all about, the vast empty plains are not there for exploration but to travel through. Rather, it’s the characters that move the story forward.

One man makes a bad decision. A lawman makes another decision. The mother figure of the person wronged is not pleased with the lawman’s decision and puts a bounty out on the men who have wronged her people. The lawman now has to deal with bounty hunters, assassins, and other vagrants moving about his peaceful town.

In helping to make the characters stand out, think of the five senses. Hearing is a good one because when the players hear the names of the characters, if the names are descriptive and appropriate, the characters will probably get it more. The Black Company and The First Law use a lot of names that make sense only in their context, like the doctor being called Croaker or the hunter with the good smell the Dogman. Here, it’s names like Skinny or Fatty that come across on even the normal people of the setting.

In terms of player character types though, the three killers, tend to fall into three separate camps.

The Kid: He comes across as tough. He has access to high quality gear. He claims a lot of deeds under his belt. But… he doesn’t seem to know things that he should. The things he does know, he learned from an older relative, a member of the old posse. He doesn’t seem as capable as he should. Those who’ve been in the field for a long time may even notice that the kid suffers from some sort of physical defect that may not be easy to notice at first. Say… being short sighted? Not a good thing for a gun fighter.

The Eternal Companion: When first introduced to Ned, he’s a friend of the Seasoned Killer. He’s okay with his past. He’s not only made peace with it, he’s moved on. He doesn’t talk about it with a lot of regret but merely as something that happened. But more importantly, he’s a keystone for the Seasoned Killer. He’s a true comrade who would face death rather than betray his friends. He may have his own specialties but he often acts as a bit of comedy relief and a mirror for the Seasoned Killer.

For example, when questioned by the Kid about facing down two marshals and coming out with only a scratch, after the Kid goes away, the Companion tells the Killer that, “I recall it was three marshals.” He’s not necessarily there to act as the conscious of the seasoned killer. Indeed, he may spur the killer on if he thinks that will get the group where they’re going, but he has limits and will not cross them, leaving his friends if in good hands, to wash the blood off his own.

The Seasoned Killer: In the movie, Munney as played by Clint Eastwood is at first a man seemingly at peace with himself. He acknowledges his foul ways. He knows that he’s done wrong. He’s pushed by circumstance to go into “one last job” but isn’t going to fall into his old ways again.

But that’s nonsense. It takes a lot for the Seasoned Killer to simmer to the top. Here, Munney endures being made a fool of by his horse. He takes it in stride for his “wickedness to animals when I was weak.” He suffers the harsh life of an outdoor travelling man in the fall season suffering rain and snow and wind. He suffers disease, his mind ravaged by fever dreams, dreaming of those he’s killed, those he knows are dead, and even his loved ones. He even suffers at the hands of Little Bill. But the encounter is too early and so, the Killer, weakened by the fever, is unable to fight at his peak and suffers a beating, worsening his condition.

And when the killer wakes up? When he throws off the beating and the fever days latter? At first he may even seem like the repentant killer. He looks about the landscape and marvels in being alive and in the beauty of a scared woman. But when it comes to the killing? No uncertainties now. Indeed, he turns out to be a better shot than his Eternal Comrade whose specialty was with that weapon. His blood turns to ice and its only on getting the job done.

Consequences? Those are for lesser men. The Seasoned Killer may be a ruthless killing machine with a cool hand, but he’s not mindless. He values his friends. When people turn on those friends, woe be unto them.

For example, here, when Munney sees his friend Ned in a coffin outside Skinny’s Bar, it’s all over for skinny. When Little Bill protest that he just shot an unarmed man, Munney replies, “He should’ve armed himself” and goes on for a second about anyone going to decorate their bar with his friend is a dead man.

This is in the midst of a room full of lawmen. This is in the middle of town. This is walking into the cave of the bear with the bear awake and pissed.

And he walks out of it with a threat to burn the town down if they don’t take care of his friend.

There are variants of the Seasoned Killer, such as Samurai X, where the character is so earnest in trying not to kill anymore, that they essentially strip themselves of the ability. But the struggle of self perception, of telling people, “I’m not like that anymore” against what the character falls back unto?

For a different example, in The First Law, the Bloody Nine noted that its difficult to change if you stay in the same place with the same people doing the same things. The old habits return and good intentions are useless.

The Seasoned Killer also has another problem that the Eternal Companion and the Kid may not. While the Companion is competent and the Kid a young blood who hasn’t made a name for himself yet, The Seasoned Killer, when identified, is a known quantity. He’s a wanted man. Those on the side of justice want him dead or behind bars and those looking for a dangerous man are willing to pay.

If you’re looking for a movie with a ton of character that has a slow built up with a great cast, Unforgiven is a solid Western.

The thing that makes Unforgiven however, is the atmosphere and the characters.

The atmosphere drifts in through names like the town, Big Whiskey and through little statements made here and there, like when someone mentions the billiards table was broken down for fire wood years ago. Or how technology isn’t there to solve every problem such as vision difficulties or simply having the hogs suffer flu.

But it is the background of the characters that helps the whole movie to gel. For example, the viewers are often introduced to characters not only through those characters actions, but by how the other individuals in the movie react to them.

When English Bob and his biographer are travelling along on the train and being taunted by one of the cowboys, another cowboy warns him that this fellow might indeed be English Bob and is not one to be trifled with. The audience is further granted a view of skills involved here with a pheasant shooting contest from the back of the moving train with Bob hitting eight and the cowboy hitting one.

But as in many setups, this is just a tease. You see, it’s a tease for the build up of Little Bill who is spoken of in near holy tones by his fellow law men. Was he scared? No. He’s a bad carpenter, but he ain’t scared. Indeed, Little Bill is so unafraid of English Bob that he gets the drop on him with a full posse and beats the crap out of him. This sets Little Bill up as a truly big bad.

One of the 4e DMGs has some advice on trying to showcase the strength of the big bad including allowing the players to take the role of the person going up against the big bad. This allows the players to first hand experience the gaming effect without the GM only having to rely on narration to showcase the strengths of the villain.

It is also the characters that move the story along. There is no dungeon to explore here. While there is a beautiful scenery all about, the vast empty plains are not there for exploration but to travel through. Rather, it’s the characters that move the story forward.

One man makes a bad decision. A lawman makes another decision. The mother figure of the person wronged is not pleased with the lawman’s decision and puts a bounty out on the men who have wronged her people. The lawman now has to deal with bounty hunters, assassins, and other vagrants moving about his peaceful town.

In helping to make the characters stand out, think of the five senses. Hearing is a good one because when the players hear the names of the characters, if the names are descriptive and appropriate, the characters will probably get it more. The Black Company and The First Law use a lot of names that make sense only in their context, like the doctor being called Croaker or the hunter with the good smell the Dogman. Here, it’s names like Skinny or Fatty that come across on even the normal people of the setting.

In terms of player character types though, the three killers, tend to fall into three separate camps.

The Kid: He comes across as tough. He has access to high quality gear. He claims a lot of deeds under his belt. But… he doesn’t seem to know things that he should. The things he does know, he learned from an older relative, a member of the old posse. He doesn’t seem as capable as he should. Those who’ve been in the field for a long time may even notice that the kid suffers from some sort of physical defect that may not be easy to notice at first. Say… being short sighted? Not a good thing for a gun fighter.

The Eternal Companion: When first introduced to Ned, he’s a friend of the Seasoned Killer. He’s okay with his past. He’s not only made peace with it, he’s moved on. He doesn’t talk about it with a lot of regret but merely as something that happened. But more importantly, he’s a keystone for the Seasoned Killer. He’s a true comrade who would face death rather than betray his friends. He may have his own specialties but he often acts as a bit of comedy relief and a mirror for the Seasoned Killer.

For example, when questioned by the Kid about facing down two marshals and coming out with only a scratch, after the Kid goes away, the Companion tells the Killer that, “I recall it was three marshals.” He’s not necessarily there to act as the conscious of the seasoned killer. Indeed, he may spur the killer on if he thinks that will get the group where they’re going, but he has limits and will not cross them, leaving his friends if in good hands, to wash the blood off his own.

The Seasoned Killer: In the movie, Munney as played by Clint Eastwood is at first a man seemingly at peace with himself. He acknowledges his foul ways. He knows that he’s done wrong. He’s pushed by circumstance to go into “one last job” but isn’t going to fall into his old ways again.

But that’s nonsense. It takes a lot for the Seasoned Killer to simmer to the top. Here, Munney endures being made a fool of by his horse. He takes it in stride for his “wickedness to animals when I was weak.” He suffers the harsh life of an outdoor travelling man in the fall season suffering rain and snow and wind. He suffers disease, his mind ravaged by fever dreams, dreaming of those he’s killed, those he knows are dead, and even his loved ones. He even suffers at the hands of Little Bill. But the encounter is too early and so, the Killer, weakened by the fever, is unable to fight at his peak and suffers a beating, worsening his condition.

And when the killer wakes up? When he throws off the beating and the fever days latter? At first he may even seem like the repentant killer. He looks about the landscape and marvels in being alive and in the beauty of a scared woman. But when it comes to the killing? No uncertainties now. Indeed, he turns out to be a better shot than his Eternal Comrade whose specialty was with that weapon. His blood turns to ice and its only on getting the job done.

Consequences? Those are for lesser men. The Seasoned Killer may be a ruthless killing machine with a cool hand, but he’s not mindless. He values his friends. When people turn on those friends, woe be unto them.

For example, here, when Munney sees his friend Ned in a coffin outside Skinny’s Bar, it’s all over for skinny. When Little Bill protest that he just shot an unarmed man, Munney replies, “He should’ve armed himself” and goes on for a second about anyone going to decorate their bar with his friend is a dead man.

This is in the midst of a room full of lawmen. This is in the middle of town. This is walking into the cave of the bear with the bear awake and pissed.

And he walks out of it with a threat to burn the town down if they don’t take care of his friend.

There are variants of the Seasoned Killer, such as Samurai X, where the character is so earnest in trying not to kill anymore, that they essentially strip themselves of the ability. But the struggle of self perception, of telling people, “I’m not like that anymore” against what the character falls back unto?

For a different example, in The First Law, the Bloody Nine noted that its difficult to change if you stay in the same place with the same people doing the same things. The old habits return and good intentions are useless.

The Seasoned Killer also has another problem that the Eternal Companion and the Kid may not. While the Companion is competent and the Kid a young blood who hasn’t made a name for himself yet, The Seasoned Killer, when identified, is a known quantity. He’s a wanted man. Those on the side of justice want him dead or behind bars and those looking for a dangerous man are willing to pay.

If you’re looking for a movie with a ton of character that has a slow built up with a great cast, Unforgiven is a solid Western.

Saturday, August 7, 2010

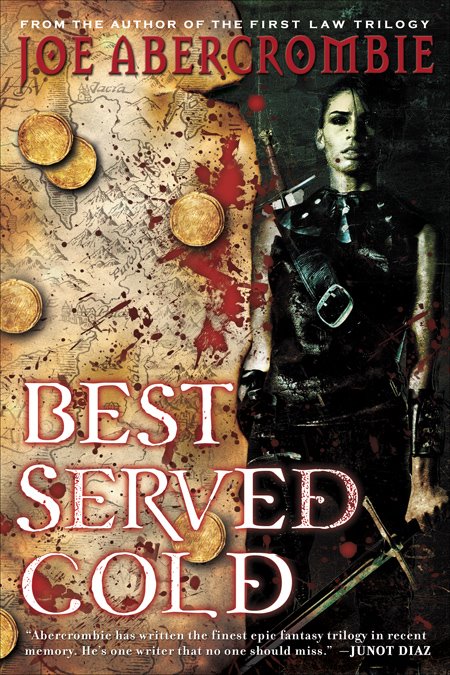

Best Served Cold by Joe Abercrombie

I'll be pulling some quotes and ideas out of Joe Abercrombie's latest book below so if you're not interested in spoilers, go no further.

It seems like just yesterday I was talking about revenge as a motivator. Here, a woman, Monza Murcatto, the Snake of Talins, who is apparently betrayed by her employer is left for dead but manages to survive the assassination attempt. But does not do so on her own.

Rather, she awakens looking a bit like ye old Frankenstein Monster with various surgeries performed on her near dead body. Nothing to augment, merely to pull the body back together. This is done by a benefactor who has his own reasons for doing so.

In that area, the GM can show some mercy to the players. If the players are facing certain death and it's not really through any fault of their own and only a few poor dice rolls or if the GM is feeling merceful, have outside sources save them at a high costs and for a price afterwards.

but does not survive without being marked. This being Joe Abercrombie, the hero is scared and less than perfect.

But it does add an interesting point in the search for vengance. While Monza is saved, she then acts as a patron for a group of assassins who are to help her in acheiving her revenge.

In terms of player opportunities, one of the characters is named Friendly. He rarely talks and is obsessed with numbers, often expressed through his rolling of the bones. These are little hooks that can be used to hang a quick identifier on. It allows you to quickly get into the mind of the character.

For those seeking to change their player, look for the opportunities in the way the story evolves. In Best Served Cold, one of the characters, Shivers, is a norseman who left the north, forsaking a blood fued against the Bloody Nine. Here, he tries to be optimistic and positive and keep a positive spin on things. His employeer, Monza, has her own theories about the way the world works based on her own experiences, some of which are quite negative, but it isn't necessarily that which wins him over. Rather, it's being taken prisoner and having his eye put out by a hot brand that turns him from an optimistic sort to a pesimisstic sort whose anger at his own employeer at the end, casues him to betray her.

Speaking of Shivers, he also provides a nice constrast to the rest of the cast in that he is a non-native to Styria. This is many ways, is similiar to the standard adventurer who goes where the adventure is. It allows the GM to explain bits and pieces of his world to the other players who may actually be from that part of the setting, but may not be familiar with it as their characters could be. The GM can give those natives bits of background information in e-mail or typed form to provide to the non-native at their own lesiure.

In terms of battle environments, there is one scene where in seeking her vengance, Monza is battling in the court yard around a massive statue known as the Warrior. It becomes damaged in the fight and it is the statue, not Monza herself that winds up killing her foe. Think about adding things that at first may not seem like they can be used to be part of the scenery, but with a few skill checks or brute damage, can wind up being the method of victory.

In my own playing days, back in 2nd edition, I was playing a wizard and the party was fighting a dragon. The thing had such a massive Magic Resistance, that I was essentially useless until I asked the GM about the roof of the cavern that we were fighting in. He allowed me to use my damaging spells on the roof to knock forth the various long hanging stones which struck the dragon like daggers. That was well before all of this 'stunting' advice and environmental awareness was being talked about. He was just a good GM that would let you roll with the situation you were in. It may not be orthodox, but try not to box the players in with their options.

In terms of plot and letting the players in, Best Served Cold opens up the scale of the setting to Monza. She is approached by a man from the Union, a banker at that, who explains to her that there are forces at work and those forces on the standard field tend to be reresented through different factions and that if she does not ally with one of them, she will not survive. And yet here a third faction presents itself, allowing Monza to actually stay out of the 'game'. This allows the GM to provide the players with an idea on how large the scope of the campaign is without actually plunging them into if they do not wish to go. It pulls back the curtain a little.

Lastly, think about the names in the setting. Monza was the leader of the Thousand Swords. A pretty spiffy name. Thanks to the constrant stream of warfare in her land, the times were known as the Years of Blood, but then because of all the looting and burning, move on to the Years of Fire. The Forgotten Realms does this with the naming of the years, each year having a different name. It can provide more context to the campaign setting.

Best Served Cold is a done in one that features several of the characters and themes and setting from Joe Abercrombie's first series, The First Law, and is well worth a read if you like your heroes dark and their enemies darker.

It seems like just yesterday I was talking about revenge as a motivator. Here, a woman, Monza Murcatto, the Snake of Talins, who is apparently betrayed by her employer is left for dead but manages to survive the assassination attempt. But does not do so on her own.

Rather, she awakens looking a bit like ye old Frankenstein Monster with various surgeries performed on her near dead body. Nothing to augment, merely to pull the body back together. This is done by a benefactor who has his own reasons for doing so.

In that area, the GM can show some mercy to the players. If the players are facing certain death and it's not really through any fault of their own and only a few poor dice rolls or if the GM is feeling merceful, have outside sources save them at a high costs and for a price afterwards.

but does not survive without being marked. This being Joe Abercrombie, the hero is scared and less than perfect.

But it does add an interesting point in the search for vengance. While Monza is saved, she then acts as a patron for a group of assassins who are to help her in acheiving her revenge.

In terms of player opportunities, one of the characters is named Friendly. He rarely talks and is obsessed with numbers, often expressed through his rolling of the bones. These are little hooks that can be used to hang a quick identifier on. It allows you to quickly get into the mind of the character.

For those seeking to change their player, look for the opportunities in the way the story evolves. In Best Served Cold, one of the characters, Shivers, is a norseman who left the north, forsaking a blood fued against the Bloody Nine. Here, he tries to be optimistic and positive and keep a positive spin on things. His employeer, Monza, has her own theories about the way the world works based on her own experiences, some of which are quite negative, but it isn't necessarily that which wins him over. Rather, it's being taken prisoner and having his eye put out by a hot brand that turns him from an optimistic sort to a pesimisstic sort whose anger at his own employeer at the end, casues him to betray her.

Speaking of Shivers, he also provides a nice constrast to the rest of the cast in that he is a non-native to Styria. This is many ways, is similiar to the standard adventurer who goes where the adventure is. It allows the GM to explain bits and pieces of his world to the other players who may actually be from that part of the setting, but may not be familiar with it as their characters could be. The GM can give those natives bits of background information in e-mail or typed form to provide to the non-native at their own lesiure.

In terms of battle environments, there is one scene where in seeking her vengance, Monza is battling in the court yard around a massive statue known as the Warrior. It becomes damaged in the fight and it is the statue, not Monza herself that winds up killing her foe. Think about adding things that at first may not seem like they can be used to be part of the scenery, but with a few skill checks or brute damage, can wind up being the method of victory.

In my own playing days, back in 2nd edition, I was playing a wizard and the party was fighting a dragon. The thing had such a massive Magic Resistance, that I was essentially useless until I asked the GM about the roof of the cavern that we were fighting in. He allowed me to use my damaging spells on the roof to knock forth the various long hanging stones which struck the dragon like daggers. That was well before all of this 'stunting' advice and environmental awareness was being talked about. He was just a good GM that would let you roll with the situation you were in. It may not be orthodox, but try not to box the players in with their options.

In terms of plot and letting the players in, Best Served Cold opens up the scale of the setting to Monza. She is approached by a man from the Union, a banker at that, who explains to her that there are forces at work and those forces on the standard field tend to be reresented through different factions and that if she does not ally with one of them, she will not survive. And yet here a third faction presents itself, allowing Monza to actually stay out of the 'game'. This allows the GM to provide the players with an idea on how large the scope of the campaign is without actually plunging them into if they do not wish to go. It pulls back the curtain a little.

Lastly, think about the names in the setting. Monza was the leader of the Thousand Swords. A pretty spiffy name. Thanks to the constrant stream of warfare in her land, the times were known as the Years of Blood, but then because of all the looting and burning, move on to the Years of Fire. The Forgotten Realms does this with the naming of the years, each year having a different name. It can provide more context to the campaign setting.

Best Served Cold is a done in one that features several of the characters and themes and setting from Joe Abercrombie's first series, The First Law, and is well worth a read if you like your heroes dark and their enemies darker.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)